Like-mindedness, whether for democracy or environmental concerns, is widely seen as the strongest engine of Europe-India relations. But important differences also deepen the rift.

EU officials tend to minimize human rights issues in India in light of India agreeing to resume the Bilateral Human Rights Dialogue suspended in 2013. However, no tangible result is expected from this dialogue and EU diplomats privately acknowledge that they will no longer be able to ignore human rights in case of further deterioration. This is already the sense of the European Parliament, where MEPs have expressed concerns on religious minorities, Kashmiris, freedom of expression, NGOs and citizenship access for Muslim refugees in an April 2021 resolution.

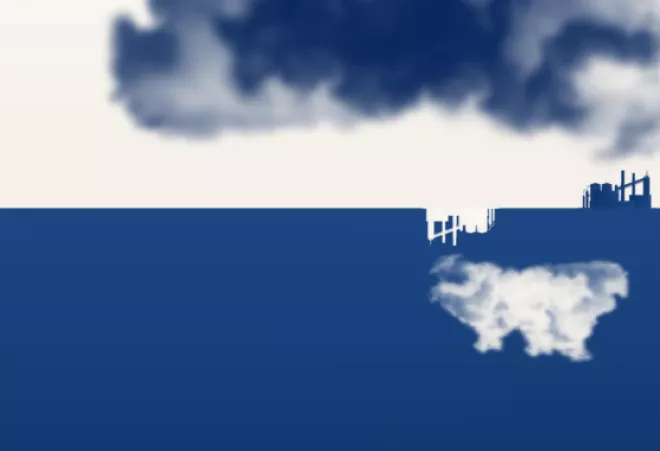

- Climate diplomacy: convergence and divergence

Like-mindedness also applies to climate. India played a very constructive role in 2015: just before the Paris meeting, it had presented its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), pledging to improve GDP emissions intensity by 33-35% below 2005 levels by 2030. India’s objectives are the same today; achieving them relies primarily on the development of renewable energy. At the COP26, Prime Minister Modi announced that India had set the target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2070. India also updated 2030 INDCs to meet 50% of its energy requirements from non-fossil fuel energy sources, and to reduce its carbon emissions by 1 billion ton.

Yet coal continues to be promoted in India; New Delhi rejected the G7 objective on net-zero emissions by 2050 in a July 2021 G20 meeting, and missed a key COP26 preparatory meeting in London. Skepticism grew at COP26, where India and China weakened pledges to phase out coal.

India does not have a decarbonization plan partly because economic growth remains a priority, if necessary at the expense of the environment. Going forward, climate action will not be an area of smooth cooperation between the EU and India.